“There are no atheists in foxholes, and no libertarians in financial crises.”

-- Paul Krugman- Economist and New York Times contributor

"In a credit crisis, a central bank should lend freely against good collateral at a high rate of interest"-- Walter Bagehot, Editor of "The Economist" in the 1860's

I've been thinking that I could and should write something about the extraordinary events of the past weeks and months, and the extraordinary request by Hank Paulson for a $700 billion dollar fund to use at the Treasury's discretion. Most of you who read this note will probably be surprised that I support the Paulson/Bernanke/Bush part of this plan. Clearly I and my industry are in "the foxhole" currently. I will not blame anyone who dismisses this note as an abandonment of principle under fire.

It is easy to point out many policy prescriptions that, had they been followed, may have prevented this mess. The mistakes at the government level were myriad 1) Massive government incentivization of home ownership 2) Massive government funding to assist homeownership 3) Legislative extortion of lenders to lend to those who should not have borrowed. 4) Persistent positive inflation causing money illusion and over-borrowing 5) Accounting Rules which were pro-cyclical and did not promote transparency or honesty. The list goes on.

However, none of this is relevant to the world that we live in. Here is the case as I see it, and how this action can be supported. Keep in mind that masochism is not policy and schadenfreude is a particularly pointless emotion. Also keep in mind that I totally disagree with Paul Krugman, and Libertarians can support action in the real world without sacrificing their beliefs. The fact is that in present form our "financial markets" are not free. For better or worse, in the wake of the Great Depression we decided that the act of providing long term credit to those who needed/demanded it was in many ways a social function that needed to be highly regulated. What we have is an intricate web of public and private actors, goals, interests, and incentives that form our financial market.

It is tough to think of a good jumping off point to explain the current financial situation, but here goes nothing. Let’s start with the fact that, our currency, the dollar, is a fiat currency. This means that our currency is NOT freely convertible into any recognized store of value (e.g. gold) AT A RATE SET BY LAW (it is of course freely convertible into almost anything at rates set by the market--a hugely important point). In other words, all that it is backed by is the full faith and credit of the U.S. government and, by extension, your tax dollars and your productivity (assuming we don't have a revolution). The Department of the Treasury is responsible for the management of the supply of this fiat currency in concert with the Federal Reserve. What does this mean?

Here is the normal, semi-Faustian bargain that the people have with the managers of a fiat currency:

1). Rational economic agents recognize that the monetary authority will permit and even desire mildly positive inflation over time because the central government will tend to run deficits and issue debt and, as the nominal value of debt is fixed, inflation will erode the real cost over time.

2). These same rational economic agents quickly learn to treat the currency as a unit of account, but not as a store of value. Immediate consumption occurs in terms of the currency, but stored productivity (savings) occurs in real or financial assets that offer positive or perhaps neutral real returns (stocks, bonds, houses, gold, coins, art, etc.)

3). As time marches on, rational economic agents additionally recognize that their wealth can be increased by borrowing in nominal terms of the unit of account, and investing the borrowed money in real assets (taking a mortgage). Lenders, in a stable positive inflationary environment, can price fixed nominal debt in such a way that they earn a positive spread over time. Everyone is happy.

Occasionally, in periods such as the years leading up to 2007, markets enter manias where flawed assumptions and flawed math lead everyone to believe that the nominal prices of certain real assets will never again go down. When everyone reaches this conclusion, there follows a massive expansion of credit as people attempt to capitalize on this opportunity to build real wealth. For the purposes of this piece, I will just assert that this happens without trying to explain its genesis. It can be seen over and over in the historical record. We have just had one of these in residential and commercial property.

What is the aftermath of such a "mania"? It is important to know the answer, because we are currently there. There comes a time when people start to realize that imprudently high prices have been paid, and perhaps the stored value of their productivity is not safe after all in their recently acquired assets. They try to sell them. If they all try at once, we have a real problem. Why? Remember that the nominal value of the debt that they incurred in the unit of account (the dollar) is fixed. However, the price of the real asset is floating (or sinking in this case). When you have a massive increase in the supply of an asset priced in dollars, the price of that asset in dollars goes down. At the same time that this is happening, lenders start to realize that some horribly imprudent loans have been made, and that they are going to have problems. They begin to call for more collateral to support the loans they have made, and to stop making new loans to protect their own balance sheets. Collateral calls force asset owners to do more selling, further depressing prices. At some point, equity in these assets (value of asset less value of debt supporting asset) disappears. When that happens, the asset owner loses all incentive to continue to pay for and manage the asset. He or she gives it back to the bank in order to satisfy the debt. This is a disaster for banks. They operate on preciously thin capital cushions. For most, an 8-10% loss of asset value would make them totally bankrupt. They do not want to own and manage real assets. They want to own paper claims on future cash flows. Banks tend to sell assets acquired this way almost immediately, perpetuating a downward price spiral. Eventually the reduced value of all the assets on the books of these banks falls below the value of their liabilities in terms of customer deposits and other borrowings. This is called insolvency, and leads to bank failures.

If the only result of these events would be that bad borrowers and bad lenders lost wealth and capital, the proper response would be to simply allow it to play out. However, the particularly vicious reality of a debt-driven asset deflation cycle such as the one I’ve laid out is that the severity of the cycle will harm otherwise prudent borrowers and lenders that potentially need not have been harmed. The Great Depression is the ultimate example of this situation. During the Great Depression, real GDP decreased by a third, and nominal GDP decreased by half. Suffice it to say, owners of assets do not retain much wealth in situations such as these, no matter how prudent they are. Outcomes such as these are truly disastrous for everyone, no matter what “street” they live on. The American people have far more debt today (and far more wealth) than they did going into the Great Depression.

Ben Bernanke is a student of the Great Depression. He knows (or believes) that the transmission mechanism which turned a business downturn and then recession 1929-1930 into the Great Depression was a debt-driven asset deflation cycle which caused a collapse in the banking system, a collapse in lending, and ultimately a collapse in the money supply. This is a view supported and promulgated by Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz in their seminal work on money and inflation. No matter how likely you think this scenario is (for the record I think it is highly unlikely), it is to be avoided at all costs. I promise you that he has no vested interest in saving “Wall Street” other than his certainty that the potential (however slight) exists for enormous pain to be felt on Main Street.

Now let’s consider Hank Paulson’s view from the Treasury. He knows America as a nation is immensely wealthy. This is because we have the most productive labor force in the world that has flourished in a mostly-free-market regulatory environment that encourages wealth creation and risk-taking. It is also partly because of, and related to, the fact that people all over the world have recognized this and lent us their money to use to create wealth. They have done this lending in exchange for debt denominated in U.S. dollars. Most of this lending (or equity financing) has been to the private sector, but a lot of it (2.5 trillion) has been foreign lending to the U.S. Government. Since the start of this financial crisis last September, the U.S. dollar has actually performed remarkably well versus the rest of the world’s currencies. The dollar is roughly unchanged over this time period. The implication of this is that while foreigners may have been selling riskier dollar-denominated assets, they have then held the cash in U.S. dollars, or used the cash to purchase U.S. Treasury bonds, which are still perceived to be the safest asset in the world in terms of retaining principal value. The nightmare scenario is that you have a debt-driven deflationary cycle which engulfs the entire financial system, causing foreigners to totally lose their faith in its integrity as a whole. The flight of capital out of dollars and out of our country would add immeasurably to the pain of any downturn. It would dramatically increase the cost of capital for every project imaginable and harm our future wealth in a way that would take a very long time to repair. No matter how you feel about “foreign capital”, the reality on the ground is that our current standard of living requires billions of dollars of it to flow into our country every single day.

Let’s fast forward to today and then talk solutions. I have chosen to take at face value the fact that Paulson and Bernanke believe that there is a non-zero and growing chance that we will have a total collapse in our banking system. The ongoing stress in the credit and interbank lending markets corroborate this reality. The price tag of such a collapse is unknowable, but suffice it to say, it would be trillions and trillions of dollars. It will make $700 billion seem like a tag sale. The Treasury hopes that by buying assets from banks that can afford to sell to them, the collapse will be averted and the system will have time to absorb its losses in a rational manner. The optimal outcome is for good banks that are currently caught in the vortex to survive, and for bad banks and managements to go out of business. In some sense the Treasury’s plan can ensure this outcome by paying a price for assets that will bankrupt imprudent banks and recapitalize and buttress prudent ones. I do not know whether or not it will work or whether or not Paulson and Bernanke are even correct about the potential for a melt down. Let’s look at four possible outcomes though:

1) Approve plan, P/B wrong about meltdown. Markets don’t collapse, perhaps the money never even gets invested, tax payers make out like bandits on what they do buy.

2) Approve plan, P/B right about meltdown. Money gets invested. Perhaps the potential meltdown is averted. If so, taxpayers make out again. If not…we have a deep and prolonged recession with awful (but perhaps lessened) consequences.

3) Vote down plan, P/B wrong about meltdown. Markets don’t collapse, we experience some further stress, we have a mild recession, and growth continues

4) Vote down plan, P/B right about meltdown. Financial disaster ensues. Trillions of dollars worth of wealth that was honestly acquired and prudently protected is destroyed. America loses its preeminent position in the world financial system. A 10-20 year depression follows.

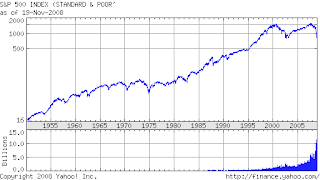

I believe alternative four is to be avoided at all costs, and further that delay is likely to cause wealth losses in this country that far exceed the $700 billion dollar price tag of this plan, even in scenario 3, no bill, no disaster. Exhibit A is the loss of 1.6 trillion in stock market wealth on Monday, along with huge losses in bond market wealth as well.

At this point it feels almost like a coda, but I believe a purely Libertarian argument can be made for this action on the grounds that the proper sphere of government is in preventing and redressing the harms that one man may inflict on all others as a direct result of his/her actions. I promise you that many many many extremely innocent players could be deeply harmed by continued forced liquidation of real assets at fire sale prices. If this causes a halt in lending, (as it already has in many cases) folks that have no debt may find themselves out of jobs they would have otherwise retained due to business failures during this downturn. The Paulson Plan could almost be seen as forced vaccination against a communicable and fatal disease (financial panic) like polio.

A pragmato-libertarian argument is that if this scenario could be prevented at a small cost to the tax payer or perhaps even at a tremendous gain, it could stave off the avalanche of increased and restrictive legislation that is certain to rain down on us in the aftermath and that could cause decades of unnecessary below-trend growth.

A purely pragmatic argument is that if Paulson is wrong, the cost is almost certain to be negligible to the tax payer, whereas if he’s right, the costs will ultimately be much much higher than $700 billion. In either case, he should have the ability and freedom to try.

You should be angry with our government and your representative for a pattern of action lasting over 70 years that was a major contributor to this problem. You should be angry that the mechanism for getting this passed seems to be stuffing it full of unnecessary goodies. There is plenty of blame to be leveled at both Wall Street and Main Street for the massive expansion of lending/borrowing which led us to this point. However, you should not let any of this stand in the way of the fact that almost no matter how small the probability of a total collapse in our banking system is, the weighted present value of such a collapse is likely to far exceed whatever losses we may all incur in an attempt to invest $700 billion dollars to unclog our banking system and allow for an expedient resumption of the necessary credit which is the engine of our financial system and economic growth.

Respectfully,

Michael W. Griswold